Design by Brett Yasko. Photo copyright © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2013

"In the Air: Visualizing What We Breathe" is a collaborative project documenting air quality in Western Pennsylvania. Photographers Scott Goldsmith, Lynn Johnson, Annie O'Neill and Brian Cohen, along with writer Reid Frazier, designer Brett Yasko and curator Laura Domencic worked together to document the social, environmental and economic factors contributing to air quality in Western Pennsylvania. The work went on exhibit in Pittsburgh in late 2015 and was featured in the New York Times "Lens" column.

"In the Air: Visualizing What We Breathe" was funded by The Heinz Endowments.

The images in this section are organized by photographer. Click on the thumbnails below to view them.

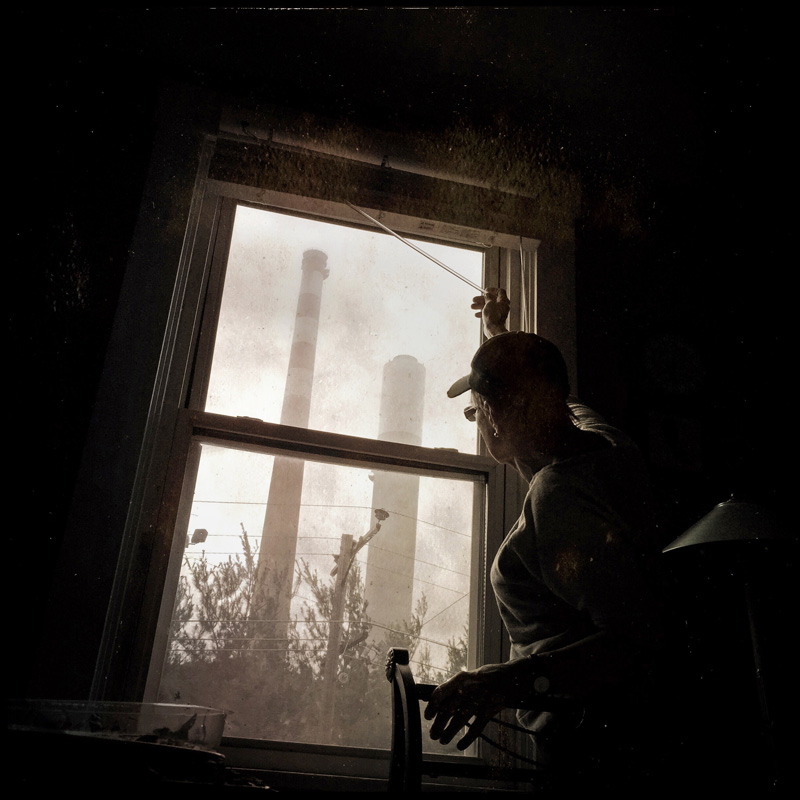

Lynn Johnson - "Ever-Present Towers"

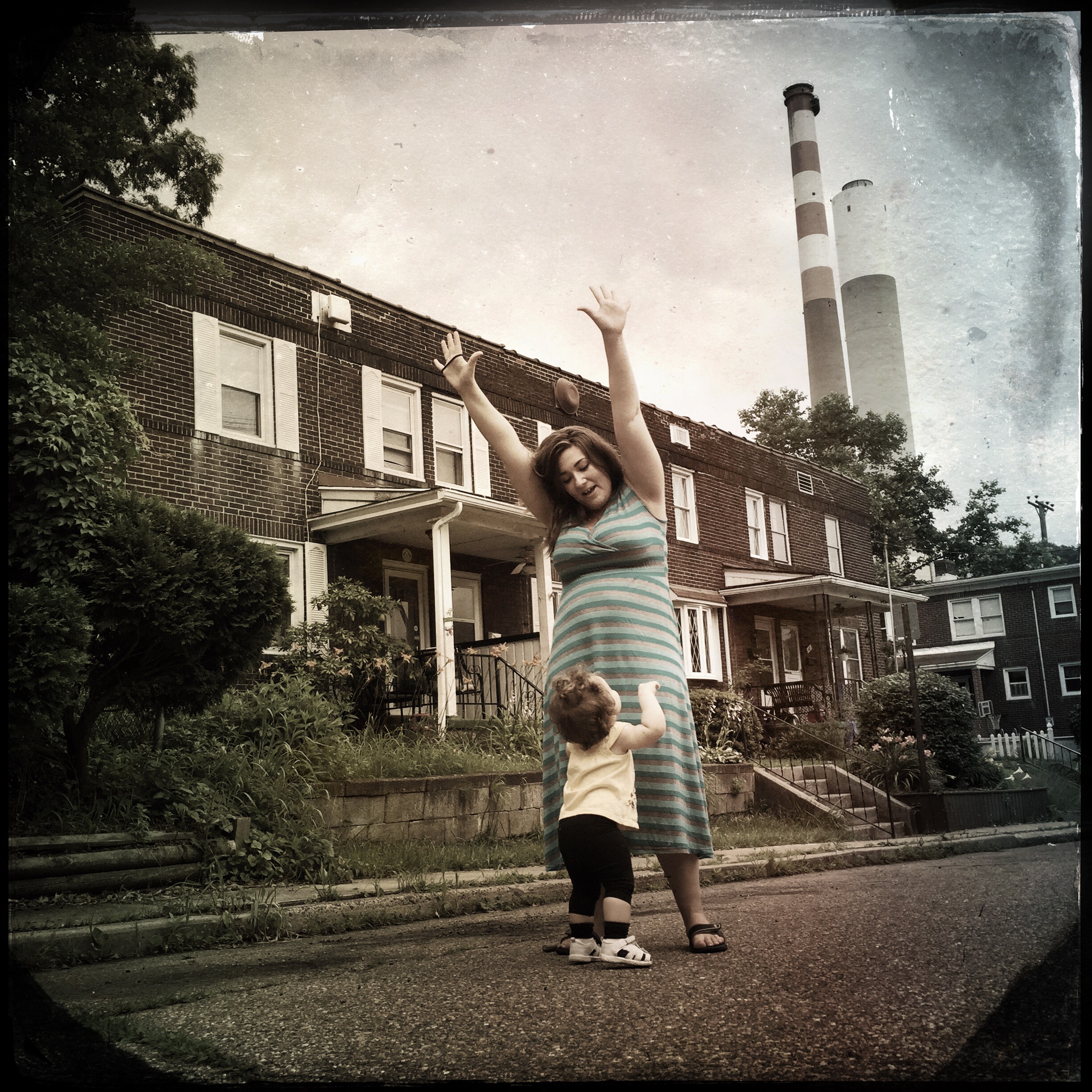

Drive into working class Cheswick, PA, walk up the hill in Springdale, float past these communities on the Allegheny River—it doesn’t matter the vantage point—they all have in common one sight: the stacks of the NRG Coal-fired Power Plant. One of 800 NRG plants across the country, its stacks can be seen from the Goodwill store and the VFW Post, from Sheetz Gas Station and Glen’s Frozen Ice Cream stand. They follow you like the eyes in a painting, around the room, around the town. The stacks’ footprint and breath are everywhere from backyard pools and parks to the grit and grime on porches, windowsills, bedroom walls. Ever present like weather or air, they have become invisible to all but a few dedicated activists.

One tower is old, silent now. The other is taller, updated with scrubbers, and belches an almost continuous plume of what appears to be roiling smoke. No one seems to know with certainty what chemicals hide in that cloud as it shoots into the atmosphere and drifts up river across the hills— out of sight and into the lungs and lawns of neighbors.

Nationwide, power plants account for 40 percent of carbon dioxide, two-thirds sulfur dioxide and 22 percent of nitrogen oxides. These and other pollutants can trigger asthma attacks, contribute to lung and heart disease. Mercury, a neurotoxin is particularly harmful to children and developing fetuses.

In a 2006 study, the Cheswick plant was rated 17th, on a list of the America’s 50 dirtiest sulfur dioxide polluters by the independent Environmental Integrity Project.

The NRG stacks are woven into the culture here. The High School football team calls them, the “stacks of doom” and chants that moniker as a war cry before taking the field. Most ironically, they can be seen from the side yard of Rachael Carson’s original homestead. The mother of environmental awareness lived just up the hill from where these vertical cannons stand today. It was there she wrote Silent Spring, a warning for the future, now our present. On a recent map that shows the spread of large and fine particle pollution from the Cheswick plant, her home is in the red zone.

Lynn Johnson - "Duquesne Court"

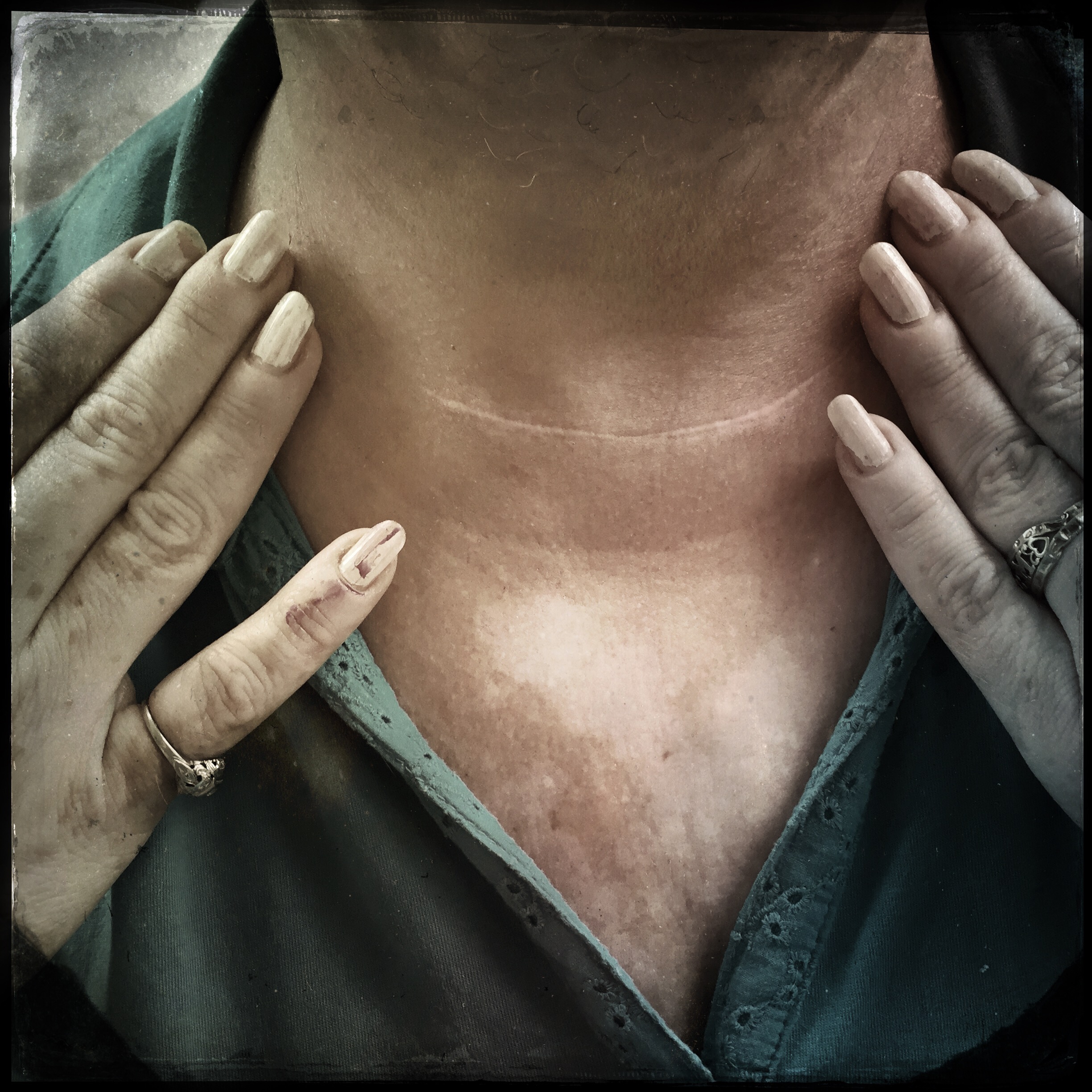

Susan, Judy, Rita, Professor Jim, Joe, Cassandra, Madison, Irene, Angelica—are among the approximately 30 families who live here in Duquesne Court. They consider each other family. The modest homes were built in the 1920’s, housing for local workers. Today the duplexes are home to working class families and retirees. Relationships are fueled by gossip and neighborhood barbeques, gardens and shared childcare. They know each other’s patterns and ailments—Rita had thyroid cancer a few years ago, one neighbor has heart issues, another can’t breathe. Two couples have lost children to chronic illness and crib death.

Most of the residents can’t afford to move. They are families starting out, retirees on fixed income and transplants that have lost their jobs and need a low rent refuge. Some are afraid to challenge NRG. Others are determined to protest its presence.

According to EPA studies, fine particle pollution from power plants contributes to thousands of premature deaths each year. Sulfur dioxide in particular can significantly harm the cardiovascular and respiratory health of people who live in the shadow of the plants. Bubbling paint on the outside of these homes makes one wonder at the condition of the inside of their bodies.

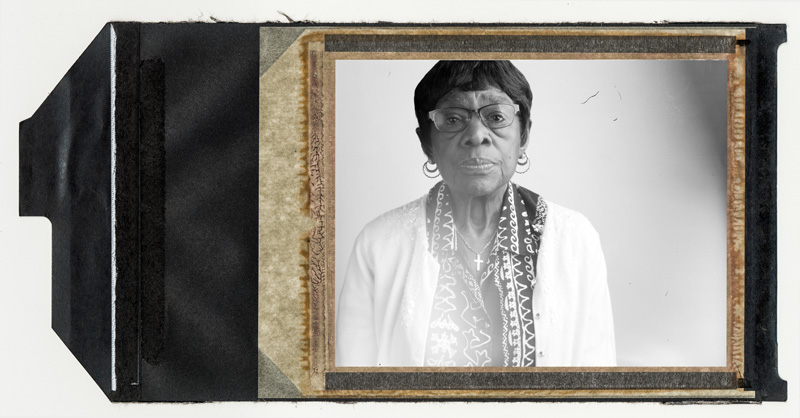

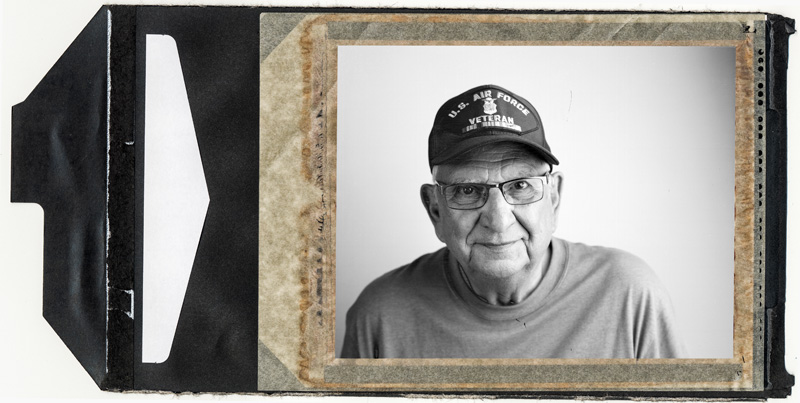

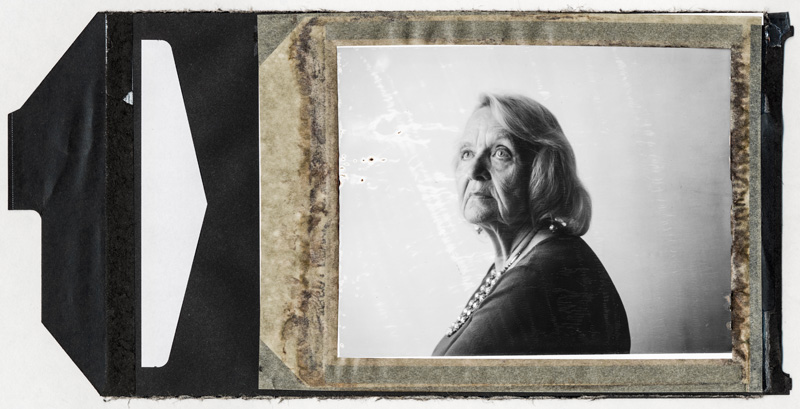

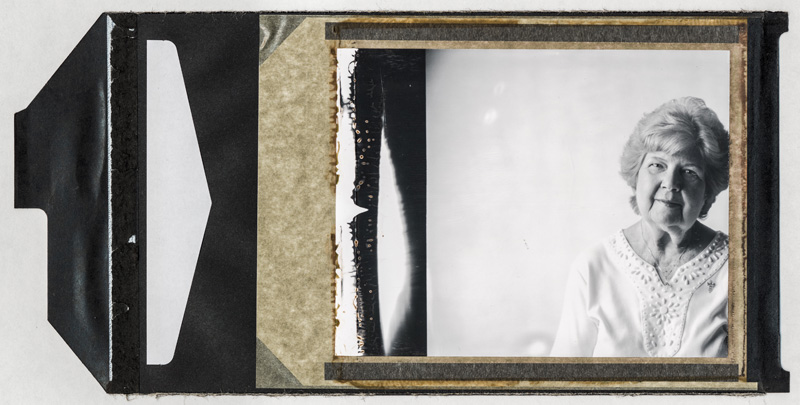

Annie O'Neill - Using 4x5 Polaroid film, Annie O'Neill created a series of portraits of survivors of the Donora smog inversion of 1948. Twenty people died over the five days of the inversion, and 7,000 more were sickened.

Rosemarie Iiams was a newly graduated pharmacy student at the time of the killer smog in Donora. She worked at a local pharmacy. “We were extremely busy at the drug store with people wanting cough medicines and an influx in prescriptions for pulmonary and breathing problems.” She believes it was a terrible thing that happened in Donora but that some good did come out of

it—the federal government started to pay attention and the air quality standards improved. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Alice Uhriniak worked as a switchboard operator in the telephone office of Donora in October of 1948. On one of the first and worst days of the crisis she started her shift at 7 am. As soon as she got in the door the women that worked the night turn said, “Hurry up get your headset on everybody is dying.” Uhriniak points out that there was no 911: the local switchboard lit up with people calling doctors, and the doctors trying to get people to the hospitals. As news spread, out-of-town relatives were calling in to get news. © Annie O'Neill 2015

After Helen Pasterick, her husband and six-month old baby watched the Halloween parade in downtown Donora, they were on their way to the movie theater when Helen was overcome by the smog and had a hard time breathing. They made a visit to Dr. William Rongus. He became well known for leading an ambulance by foot through the darkened streets to help the dying and sick. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Faustina Jakela grew up in Donora. She 10 years old in 1948. Her most vivid memory of the inversion was being woken up by a phone call and hearing the news that her father had collapsed in front of the laundromat only a few blocks from home. He was walking to work at the zinc plant where he worked the 11 pm shift. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Marie Gardner lived right next to the zinc plant. She was thirteen years old in October 1948 and was a housekeeper for one of the bosses of the mill. “I just thought it was just a heavy fog—F-O-G. We never heard of smog. I remember having a sweet taste in my mouth from the air and I remember walking home in that crap. But I don’t’ think it affected me much because I was young and did not smoke.” © Annie O'Neill 2015

Former Donora mayor Anthony Massafra takes credit for starting the slogan, “Clean Air started here.” He was referring to the federal clean-air laws that started after the smog incident. He was seventeen years old and a high-school senior at the time. It was during a Halloween parade on McKean Avenue that people started to realize something was wrong. He said they could hardly see the marchers in the parade, let alone the people across the street. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Edith Jericho was twelve years old when the smog blanketed Donora. She lived across the river in Webster where her father, James Troy, would walk to work at the zinc plant. She has a strong memory of him wearing a wet bandana over his nose and mouth during those five days of the smog. Jericho said she will never forget her neighbor running over to their home early one morning of the smog and yelling to her mom, “Miss Annie, Miss Annie, come quick! There is something wrong with my Emma.” When her mother went to check, she found she was dead. Emma Hobbs was fifty-five. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Pat Gillingham has lived in historic Cement City of Donora since she was six months old. She was a senior in high school at the time of the smog. Her family’s reaction was similar to that of many Donora residents. “We did not realize anything was wrong. We thought it was just a normal fog.” The family did not realize how bad it was until they received calls from out-of-town family asking how they were doing. The relatives had heard news reports of the fatalities. © Annie O'Neill 2015

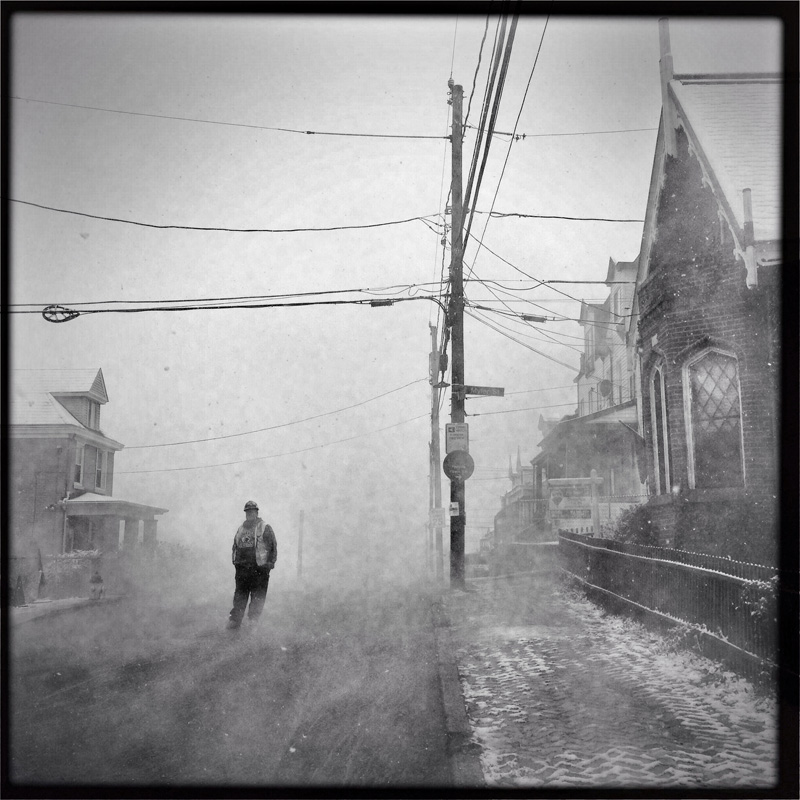

Scott Goldsmith - the social and environmental effects of poor air quality.

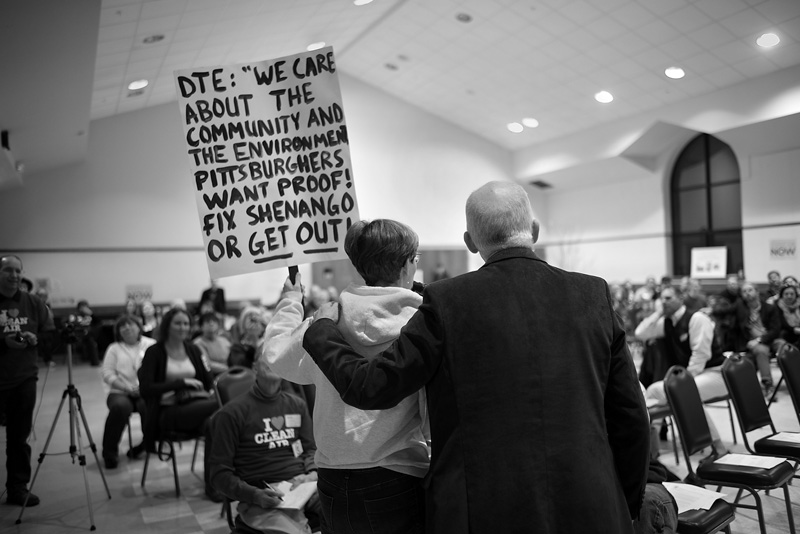

Fog, smoke, and air inversion often create a perfect setting for bad air quality along the Ohio River near the Shenango Inc. coke works. Residents living nearby have the highest rates of asthma in Allegheny County. Coke oven fuel made from coal emits various toxins along with odors and smoke. Pittsburgh has some of the worst fine-particle pollution in the nation, due in part to the presence of several coke plants in close proximity. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2004

Supporters of EPA regulations against power plant carbon emissions rally in front of theAugust Wilson Center in Downtown Pittsburgh on Thursday, July 31, 2014. About 300 environmental activists yell their support for stricter pollution rules proposed by the Environmental Protection Agency during a march to the Pittsburgh Federal Building by about 5,000 people, led by the United Mine Workers of America, during a two-day public hearing being held by the EPA.. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2014

United Mine Worker Floyd Macheska from West Newton, PA, and his grandson Stephen Macheska, nine, from Belle Vernon, PA, watch as fourteen members of the United Mine Workers of America are arrested after refusing to move from the steps of the Federal Building. Some 5,000 union members led by the UMWA marched to protest stricter pollution rules for coal-burning power plants proposed by the EPA... © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2014

Clairton High School head coach Tom Nola addresses one of his players after a mistake during a game. Over the years, this team is regularly the best in Pennsylvania. Yet asthma is a problem known well by football players at Clairton Middle and High School, one of the smallest and poorest in the state and home to the nation’s largest coke plant, just 12 miles south of Pittsburgh. Many of the players bring inhalers to practice and games; 18.2 percent of Clairton students have asthma (national rates are 8 percent for adults and 9.3 percent for children). The football team rate is a little higher. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2014

Christine Pollachi breaks down during a meeting with the EPA. She was explaining her health problems caused by bad air from Shenango Inc. coke works. Emissions from coke plants include benzene and other carcinogens, hydrogen sulfide, and significant quantities of particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, and sulfur dioxide. This coke plant is less than 1 mile from the densely populated communities of Ben Avon (where Pollachi is from), Avalon, Bellevue and Emsworth — and less than 5 miles from Downtown Pittsburgh. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2014

Neville Island on a bad ozone day caused by air inversion, contamination from

Shenango Inc. coke works (smoke stack in upper middle left) and diesel engine emissions. Shenango has been the subject of numerous lawsuits and consent orders for decades. The coke works operates twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Asthma rates in the school district closest to Shenango are the highest in Allegheny County. The Clairton Plant can be seen on the distant horizon top right. Small flares from Shale gas rigs can be seen as tiny flames. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2014

A train derailment in Uniontown, PA in 2015. One car landed 6 feet from a nearby house, spilling frack sand around it. Frack sand is used during the hydraulic fracturing process and is hazardous to human health. The particulates are so small and oddly shaped that they seldom release from the lungs and can cause many respiratory problems including lung cancer. Sand was still pouring from the train cars two hours after the accident. Residents were not warned of potential respiratory problems and the workers who cleaned it up did not wear breathing protection. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2015

A train derailment in Uniontown, PA in 2015. One car landed 6 feet from a nearby house, spilling frack sand around it. Frack sand is used during the hydraulic fracturing process and is hazardous to human health. The particulates are so small and oddly shaped that they seldom release from the lungs and can cause many respiratory problems including lung cancer. Sand was still pouring from the train cars two hours after the accident. Residents were not warned of potential respiratory problems and the workers who cleaned it up did not wear breathing protection. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2015

This house, in Blairsville, PA, is about a mile from the coal-fired generating plant at Homer City. Asthma rates here are high; incidence of heart ailments are higher than average. Pennsylvania’s power plants are the third most polluting in the country, and are the single largest source of carbon pollution, responsible for 48 percent of emissions statewide. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2015

A train loaded with crude oil rolls past the Shenango Inc. coke works near Pittsburgh, PA. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency describes coke oven emissions as “among the most toxic of all air pollutants.” The train is carrying crude oil from the Bakkan oil field in North Dakota. These trains have derailed numerous times across the U.S. causing extreme air and water pollution. The oil they carry will be burned for energy, causing further release of fine particulates. The trains themselves become air polluters along the route. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2015

Linda Dever suffers from COPD and came to the ER at Allegheny General Hospital suffering a respiratory attack. While it is hard to pinpoint the cause of her respiratory problems, she lives close to Shenango Inc. coke works and has increased symptoms on high ozone days. The American Allergy and Asthma Foundation ranks Pittsburgh the fourth most challenging place to live with asthma in the nation, listing air pollution and the number of ozone alert days among the chief reasons why. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2015

Elizabeth Sandhagen lives in southern Allegheny County and must stay inside most of the time because of severe breathing problems. She uses a specialized inhaler and receives a monthly injection to keep her lung passages open. The drug—a strong antihistamine that can cause unexpected anaphylactic shock—is thick and must be administered via a large needle which causes her pain. Sandhagen’s respiratory problems dissipate significantly when she leaves

Western PA. She feels the air particulates levels in Allegheny County are the cause of her problems. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2015

Elizabeth Sandhagen lives in southern Allegheny County and must stay inside most of the time because of severe breathing problems. She uses a specialized inhaler and receives a monthly injection to keep her lung passages open. The drug—a strong antihistamine that can cause unexpected anaphylactic shock—is thick and must be administered via a large needle which causes her pain. Sandhagen’s respiratory problems dissipate significantly when she leaves

Western PA. She feels the air particulates levels in Allegheny County are the cause of her problems. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2015

The Homer City Generating Station is one of the top five most polluting power plants in Pennsylvania, which has the third most polluting plants in the country. Pennsylvania’s power plants are its single largest source of carbon pollution—responsible for 48 percent of statewide emissions. The country’s biggest air polluters are challenging an EPA measure that would force roughly 600 coal- and oil-fired power plants to reduce the amount of mercury, arsenic, and other toxic metals and gases they let escape into the air, lakes, and rivers. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2015

A boy playing with fireworks in the Bellevue borough of Pittsburgh. A new NOAA study shows that Fourth of July fireworks temporarily increase particulate pollution by an average of 42 percent. The effect is worse in the Pittsburgh area because of trapped air due to inversions. © Scott Goldsmith/TDW 2009

Brian Cohen - air quality and the landscape of south-western Pennsylvania.

Carrie Furnace is the last remaining unused blast furnace in the Pittsburgh area. It was built in 1881; furnaces 6 and 7, all that remain, functioned from 1908 to 1978, when the plant was shut down. Carrie made iron for the Homestead Works, at its peak employing approximately 2,400 people and producing over 1,000 tons of iron a day. © Brian Cohen, 2011.

Conemaugh coal-fired power plant, in Indiana County, began operation in the early 1970s. Run by a subsidiary of GenOn Energy Inc., it burns more than 4 million tons of coal a year. According to Wikipedia, “In March 2011, PennEnvironment and the Sierra Club won a favorable court ruling finding that the plant had committed 8,684 violations of the Clean Water Act by discharging waste directly into the Conemaugh River.” © Brian Cohen, 2015.

At the time this project was in production, the Shenango Inc. coke works on Neville Island was under a court order to reduce emissions. During a period of 432 days between July 2012 and September 2013, the coke works on Neville Island was in violation for 330 days. In December, 2015, it was announced that the plant would shut down. © Brian Cohen, 2014.

United States Steel Corporation, Clairton Coke Works is the largest coke manufacturing facility in the U.S. Part of the Mon Valley Works, it lies on the Monongahela River about 15 miles southeast of Pittsburgh. According to a September 2014 article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “U.S. Steel Corp.’s $1.2 billion upgrade of its Clairton Coke Works was supposed to significantly reduce air pollution, but some of the new equipment isn’t working as expected and has been in continuous violation of air emissions limits since its startup in November 2012.” © Brian Cohen, 2015.

Carrie Furnace is the last remaining unused blast furnace in the Pittsburgh area. It was built in 1881; furnaces 6 and 7, all that remain, functioned from 1908 to 1978, when the plant was shut down. Carrie made iron for the Homestead Works, at its peak employing approximately 2,400 people and producing over 1,000 tons of iron a day. © Brian Cohen, 2011.

On the Monongahela River about 15 miles southeast of Pittsburgh, United States Steel Corporation's Clairton Coke Works is the largest coke manufacturing facility in the U.S. In January, 2015, the environmental non-profit PennFuture, announced legal action against U.S. Steel for violations of county, state, and federal clean air laws at the Clairton Coke Works. © Brian Cohen, 2015.

The quality and quantity of cloud cover across the globe has changed since the industrial period. In the simplest of terms, the skies were clearer in pre-industrial times; the burning of fossil fuels is the principle activity that affects both cloud formation and local climates. Anthroclouds – clouds formed by human activity – are a phenomenon associated with, amongst other things, thermal power plants such as the Homer City generating station, pictured here. © Brian Cohen, 2015.

Homer City coal-fired power plant in Indiana County generates enough energy to power two million homes. According to Wikipedia, in 1995 Homer City put out 127,383 pounds (57.780 metric tons) of sulfur dioxide (SO2); though scrubbers were installed in 1998, in 2003 Homer City was ranked the fourth worst SO2 polluter in the nation, putting out 151,262 pounds (68.611 metric tons) of SO2. More scrubbers were installed in 2012.. © Brian Cohen, 2011.

At the time this project was in production, the Shenango Inc. coke works on Neville Island was under a court order to reduce emissions. During a period of 432 days between July 2012 and September 2013, the coke works on Neville Island was in violation for 330 days. In December, 2015, it was announced that the plant would shut down. © Brian Cohen, 2015.

Little Blue Run Lake is a coal ash impoundment for waste piped seven miles from the Bruce Mansfield power plant in Shippingport. It is the largest such site in the United States, containing twenty billion of gallons of coal ash waste. Coal ash contains toxins such as mercury and selenium; the reason for the aquamarine color of the water is disputed, but likely due to the presence of heavy metals such as cadmium. Despite containing many harmful substances, coal ash is not regulated as hazardous waste by the EPA. © Brian Cohen, 2015.

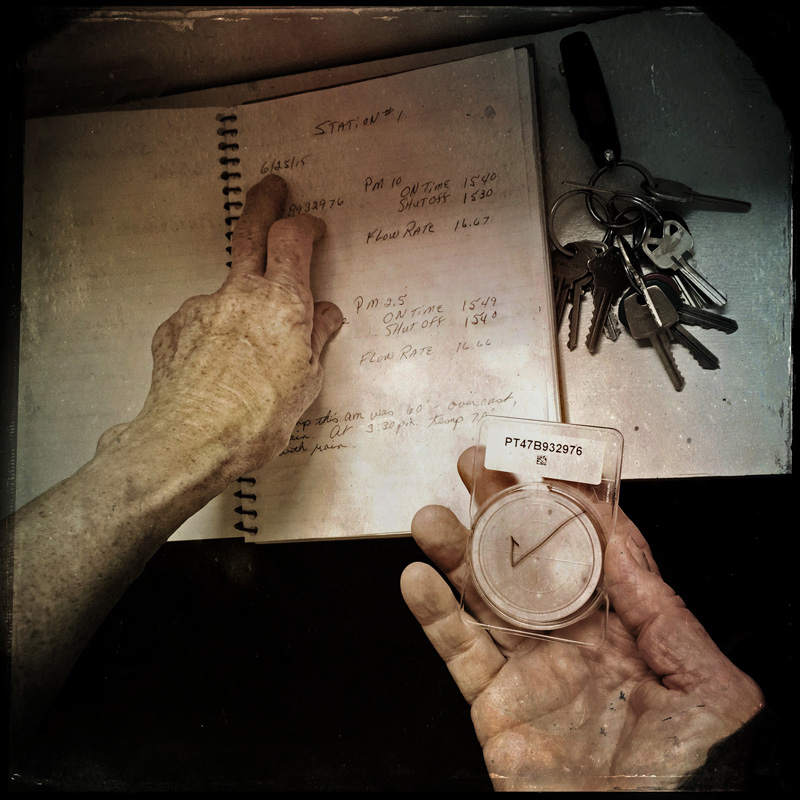

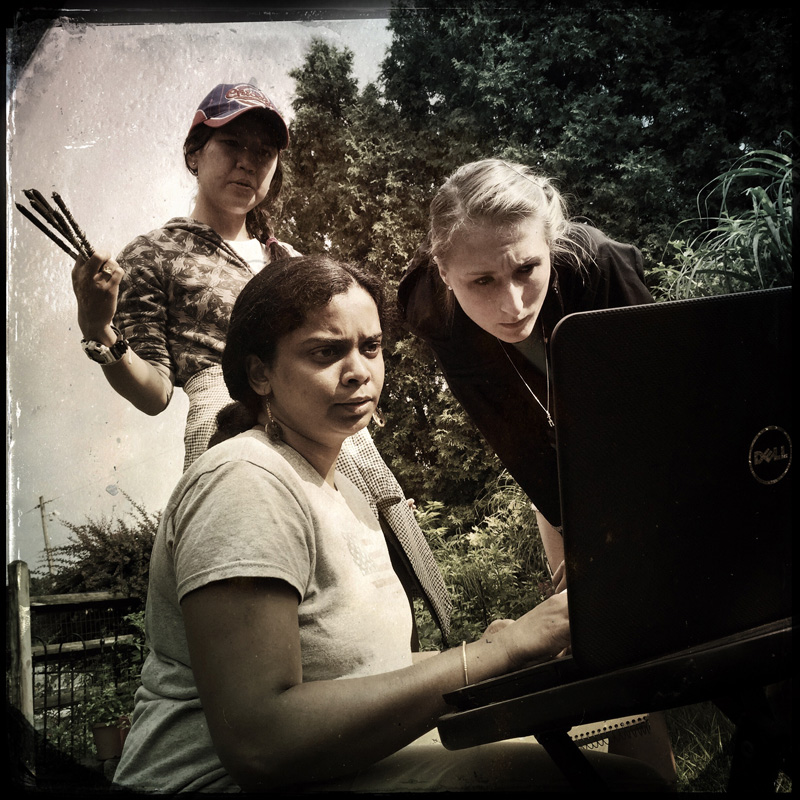

Lynn Johnson - "activists"

There is a small cadre of activists who monitor air quality in the Cheswick and Springdale areas. They are supported by the local Sierra Club, and a team of environmental scientists and graduate students from the University of North Carolina.

The first images are of Marti Blake. She lives directly across the street from the NRG plant and can see the stacks from her bedroom window. She is tired of the grit in her home, tired of asthma attacks and environmental allergies. This summer she faithfully recorded data about weather, and particulates gathered by instruments planted in residential neighborhoods around the community.

On occasion, Dr. Viney Aneja, a professor of environmental technology, and his team of graduate students, led by Priya Pillai, make the trek from North Carolina to carefully move the testing equipment from one secluded yard to another. Test results are due in Fall of 2015.

Annie O'Neill - mobile asthma clinic, and snapshots of air.

Rose Lanzo (left), a research coordinator at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC gives Alivia Thomas a refresher on how to use her inhaler and spacer in the Ronald McDonald Care Mobile. The

Care Mobile makes it easier for the patients by bringing the medical care to them. © Annie O'Neill/TDW 2015

Theodore “Ted” Popovich, a resident of Ben Avon, PA and co-founder of ACCAN—

Allegheny County Clean Air Now—is on a mission to close the Shenango Inc. coke works, one of the heaviest polluters in Allegheny County. The plant was closed in later 2015; Shenango, Inc., claimed it was no loner economically viable. © Annie O'Neill/TDW 2015

Members of GASP: Group Against Smog and Pollution, CAPS: Center for Atmospheric Particle Studies and ACCAN: Allegheny County Clean Air Now meet on the Neville Island Bridge. The groups were there to learn how to “read smoke” coming out of the Shenango Inc. coke works. Smoke readers are certified to recognize and understand visible emissions from smoke stacks. © Annie O'Neill/TDW 2015

Angelo Taranto (left) of ACCAN: Allegheny County Clean Air Now takes shelter in a car from the bitter cold on a January day to “read” the smoke emissions from the Shenango Inc. coke plant on Neville Island. Taranto is a certified smoke reader. He is trained to read and understand the different types of smoke emitted from smoke stacks. Bin Xie (right), a student at Carnegie Mellon University, observes. © Annie O'Neill/TDW 2015

Umbrellas frame an exhaust pipe at a Pittsburgh North Siderestaurant; glass hummingbirds dangle from a tree across from the power plant in Cheswick,

PA; the reflection of lace hanging in the windows of the Rachel Carson homestead can be seen in a portrait of the famous conservationist, who grew up in Springdale, PA, about 17 miles from Pittsburgh, and whose book, Silent Spring, and other works are credited with awakening many to environmental issues; fresh tar is applied to the streets of Pittsburgh’s Fineview neighborhood. © Annie O'Neill/TDW 2015

The reflection of lace hanging in the windows of the Rachel Carson homestead can be seen in a portrait of the famous conservationist, who grew up in Springdale, PA, about 17 miles from Pittsburgh, and whose book, Silent Spring, and other works are credited with awakening many to environmental issues. © Annie O'Neill/TDW 2015

Umbrellas frame an exhaust pipe at a Pittsburgh North Siderestaurant; glass hummingbirds dangle from a tree across from the power plant in Cheswick,

PA; the reflection of lace hanging in the windows of the Rachel Carson homestead can be seen in a portrait of the famous conservationist, who grew up in Springdale, PA, about 17 miles from Pittsburgh, and whose book, Silent Spring, and other works are credited with awakening many to environmental issues; fresh tar is applied to the streets of Pittsburgh’s Fineview neighborhood. © Annie O'Neill/TDW 2015

The coal dust trapped for decades inside the walls of a Pittsburgh North Side home is released during demolition and settles on John, a demo worker; Anthony Massafra, former Mayor of Donora, PA, walks down McKean Avenue where, for five days in October 1948, a smog blanketed Donora; twenty people died, thousands were stricken, and fifty more died within a month of the incident; condensation forms on windows at a Western Pennsylvania golf course on a July afternoon. © Annie O'Neill/TDW 2015

In years past, the pollution of the city of Pittsburgh was easy to see—hence the nickname The Smoky City.” In recent years, a lot of the highly visible pollution has been cleaned up, leading people to believe the air quality is good. But Pittsburgh often rates as one of the worst cities for air quality in America because of the microscopic, invisible pollution in the air. © Annie O'Neill/TDW 2015