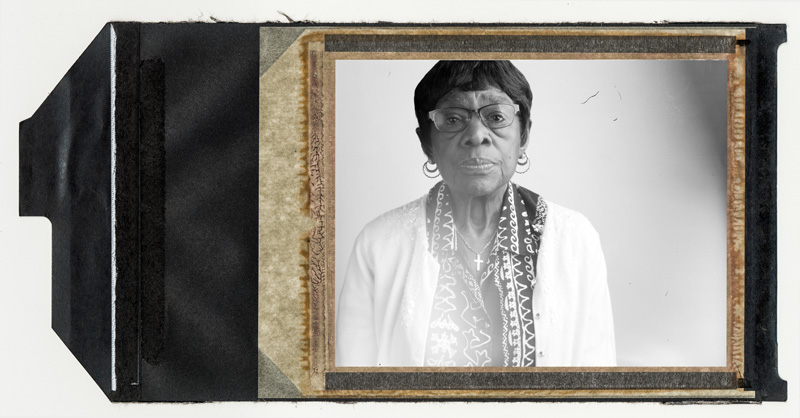

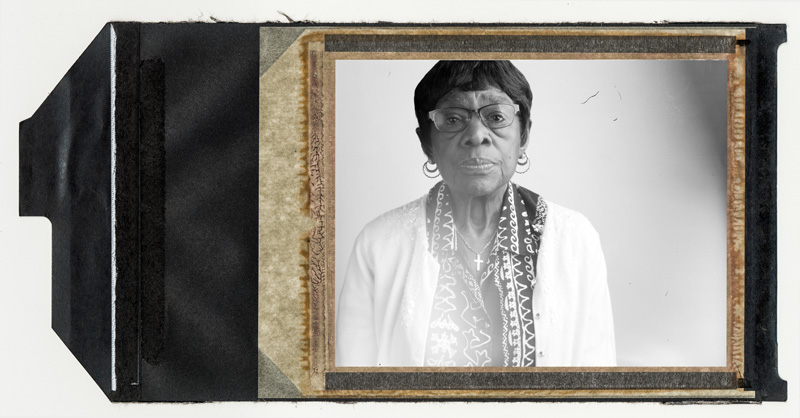

Rosemarie Iiams was a newly graduated pharmacy student at the time of the killer smog in Donora. She worked at a local pharmacy. “We were extremely busy at the drug store with people wanting cough medicines and an influx in prescriptions for pulmonary and breathing problems.” She believes it was a terrible thing that happened in Donora but that some good did come out of

it—the federal government started to pay attention and the air quality standards improved. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Alice Uhriniak worked as a switchboard operator in the telephone office of Donora in October of 1948. On one of the first and worst days of the crisis she started her shift at 7 am. As soon as she got in the door the women that worked the night turn said, “Hurry up get your headset on everybody is dying.” Uhriniak points out that there was no 911: the local switchboard lit up with people calling doctors, and the doctors trying to get people to the hospitals. As news spread, out-of-town relatives were calling in to get news. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Joan Reis was 10 years old during the inversion. She grew up in Fellsburg, five miles from Donora. Her grandfather lived directly across from the mills and became very ill from the smog. He had to live with her family for a few weeks until he recovered. © Annie O'Neill 2015

After Helen Pasterick, her husband and six-month old baby watched the Halloween parade in downtown Donora, they were on their way to the movie theater when Helen was overcome by the smog and had a hard time breathing. They made a visit to Dr. William Rongus. He became well known for leading an ambulance by foot through the darkened streets to help the dying and sick. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Faustina Jakela grew up in Donora. She 10 years old in 1948. Her most vivid memory of the inversion was being woken up by a phone call and hearing the news that her father had collapsed in front of the laundromat only a few blocks from home. He was walking to work at the zinc plant where he worked the 11 pm shift. © Annie O'Neill 2015

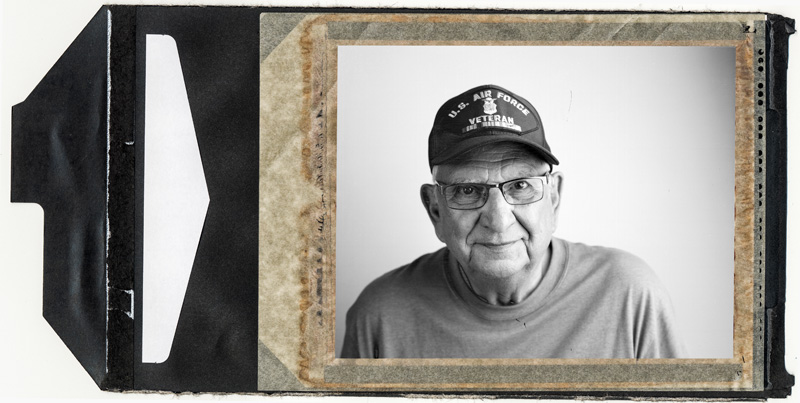

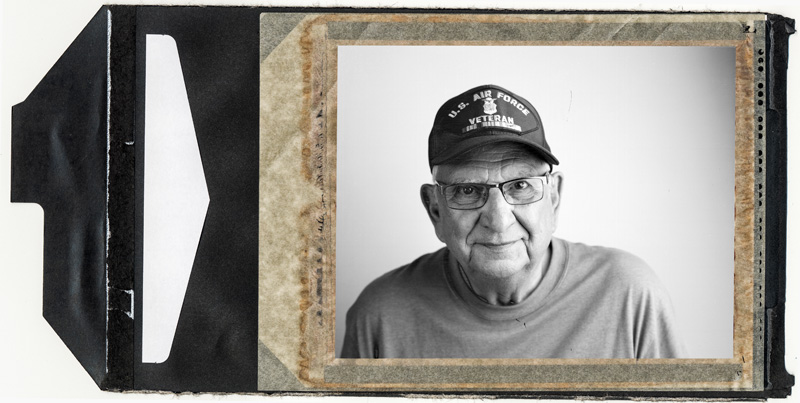

Bernard Adamek said he does not have a great memory of the smog. He thinks there has been way too much of a big deal made of it all. He said Donora was always foggy and it seemed like most days. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Marie Gardner lived right next to the zinc plant. She was thirteen years old in October 1948 and was a housekeeper for one of the bosses of the mill. “I just thought it was just a heavy fog—F-O-G. We never heard of smog. I remember having a sweet taste in my mouth from the air and I remember walking home in that crap. But I don’t’ think it affected me much because I was young and did not smoke.” © Annie O'Neill 2015

Former Donora mayor Anthony Massafra takes credit for starting the slogan, “Clean Air started here.” He was referring to the federal clean-air laws that started after the smog incident. He was seventeen years old and a high-school senior at the time. It was during a Halloween parade on McKean Avenue that people started to realize something was wrong. He said they could hardly see the marchers in the parade, let alone the people across the street. © Annie O'Neill 2015

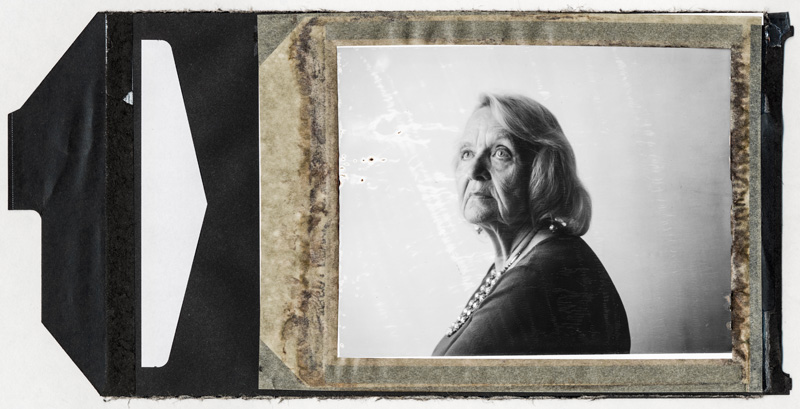

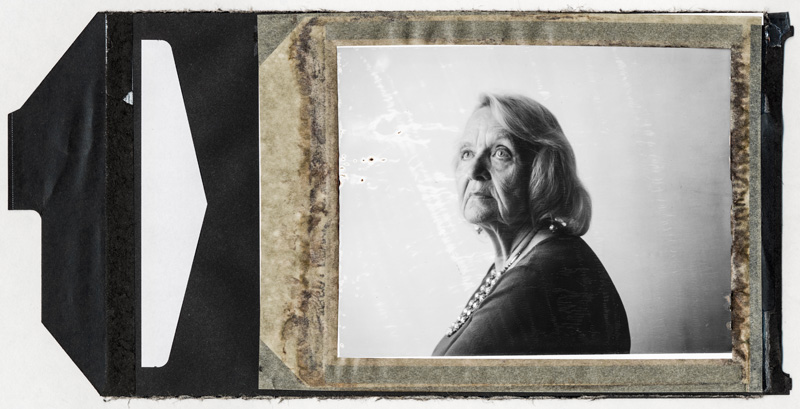

Edith Jericho was twelve years old when the smog blanketed Donora. She lived across the river in Webster where her father, James Troy, would walk to work at the zinc plant. She has a strong memory of him wearing a wet bandana over his nose and mouth during those five days of the smog. Jericho said she will never forget her neighbor running over to their home early one morning of the smog and yelling to her mom, “Miss Annie, Miss Annie, come quick! There is something wrong with my Emma.” When her mother went to check, she found she was dead. Emma Hobbs was fifty-five. © Annie O'Neill 2015

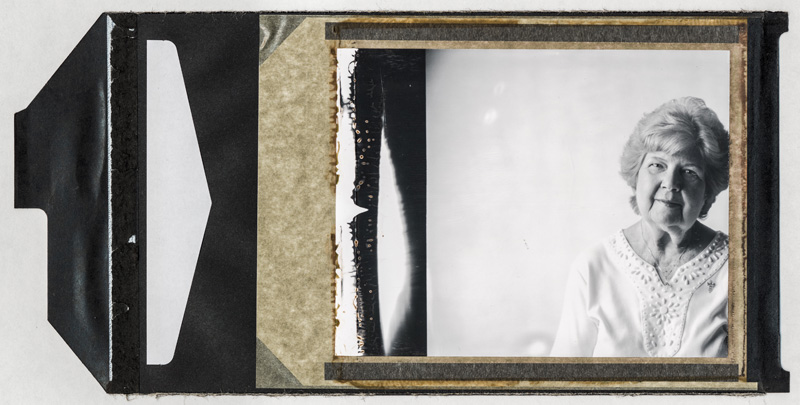

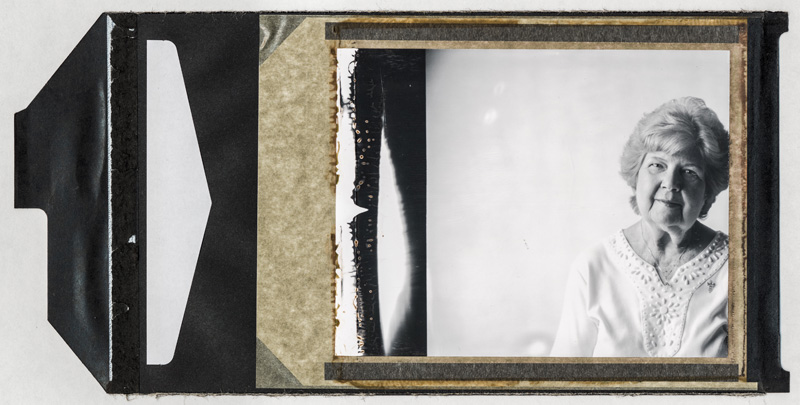

Pat Gillingham has lived in historic Cement City of Donora since she was six months old. She was a senior in high school at the time of the smog. Her family’s reaction was similar to that of many Donora residents. “We did not realize anything was wrong. We thought it was just a normal fog.” The family did not realize how bad it was until they received calls from out-of-town family asking how they were doing. The relatives had heard news reports of the fatalities. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Rosemarie Iiams was a newly graduated pharmacy student at the time of the killer smog in Donora. She worked at a local pharmacy. “We were extremely busy at the drug store with people wanting cough medicines and an influx in prescriptions for pulmonary and breathing problems.” She believes it was a terrible thing that happened in Donora but that some good did come out of

it—the federal government started to pay attention and the air quality standards improved. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Alice Uhriniak worked as a switchboard operator in the telephone office of Donora in October of 1948. On one of the first and worst days of the crisis she started her shift at 7 am. As soon as she got in the door the women that worked the night turn said, “Hurry up get your headset on everybody is dying.” Uhriniak points out that there was no 911: the local switchboard lit up with people calling doctors, and the doctors trying to get people to the hospitals. As news spread, out-of-town relatives were calling in to get news. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Joan Reis was 10 years old during the inversion. She grew up in Fellsburg, five miles from Donora. Her grandfather lived directly across from the mills and became very ill from the smog. He had to live with her family for a few weeks until he recovered. © Annie O'Neill 2015

After Helen Pasterick, her husband and six-month old baby watched the Halloween parade in downtown Donora, they were on their way to the movie theater when Helen was overcome by the smog and had a hard time breathing. They made a visit to Dr. William Rongus. He became well known for leading an ambulance by foot through the darkened streets to help the dying and sick. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Faustina Jakela grew up in Donora. She 10 years old in 1948. Her most vivid memory of the inversion was being woken up by a phone call and hearing the news that her father had collapsed in front of the laundromat only a few blocks from home. He was walking to work at the zinc plant where he worked the 11 pm shift. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Bernard Adamek said he does not have a great memory of the smog. He thinks there has been way too much of a big deal made of it all. He said Donora was always foggy and it seemed like most days. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Marie Gardner lived right next to the zinc plant. She was thirteen years old in October 1948 and was a housekeeper for one of the bosses of the mill. “I just thought it was just a heavy fog—F-O-G. We never heard of smog. I remember having a sweet taste in my mouth from the air and I remember walking home in that crap. But I don’t’ think it affected me much because I was young and did not smoke.” © Annie O'Neill 2015

Former Donora mayor Anthony Massafra takes credit for starting the slogan, “Clean Air started here.” He was referring to the federal clean-air laws that started after the smog incident. He was seventeen years old and a high-school senior at the time. It was during a Halloween parade on McKean Avenue that people started to realize something was wrong. He said they could hardly see the marchers in the parade, let alone the people across the street. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Edith Jericho was twelve years old when the smog blanketed Donora. She lived across the river in Webster where her father, James Troy, would walk to work at the zinc plant. She has a strong memory of him wearing a wet bandana over his nose and mouth during those five days of the smog. Jericho said she will never forget her neighbor running over to their home early one morning of the smog and yelling to her mom, “Miss Annie, Miss Annie, come quick! There is something wrong with my Emma.” When her mother went to check, she found she was dead. Emma Hobbs was fifty-five. © Annie O'Neill 2015

Pat Gillingham has lived in historic Cement City of Donora since she was six months old. She was a senior in high school at the time of the smog. Her family’s reaction was similar to that of many Donora residents. “We did not realize anything was wrong. We thought it was just a normal fog.” The family did not realize how bad it was until they received calls from out-of-town family asking how they were doing. The relatives had heard news reports of the fatalities. © Annie O'Neill 2015